Range Rovers across the Darien

“I jump out of the Range Rover, and, as I’m taking the ladders off the roof, our doctor yells, ‘Look out, behind you!’ There’s a fer de lance snake by my foot. Small, brown, deadly. No antidote. The bloody thing strikes my boot, into the leather, just below bare skin. As it rears up to strike again, the doc leaps out with a machete and lops its head off…”

Meet Gavin Thompson, the army officer who, in the spring of 1972, led the first-ever successful vehicle expedition through the world’s most inhospitable terrain: the Darién Gap.

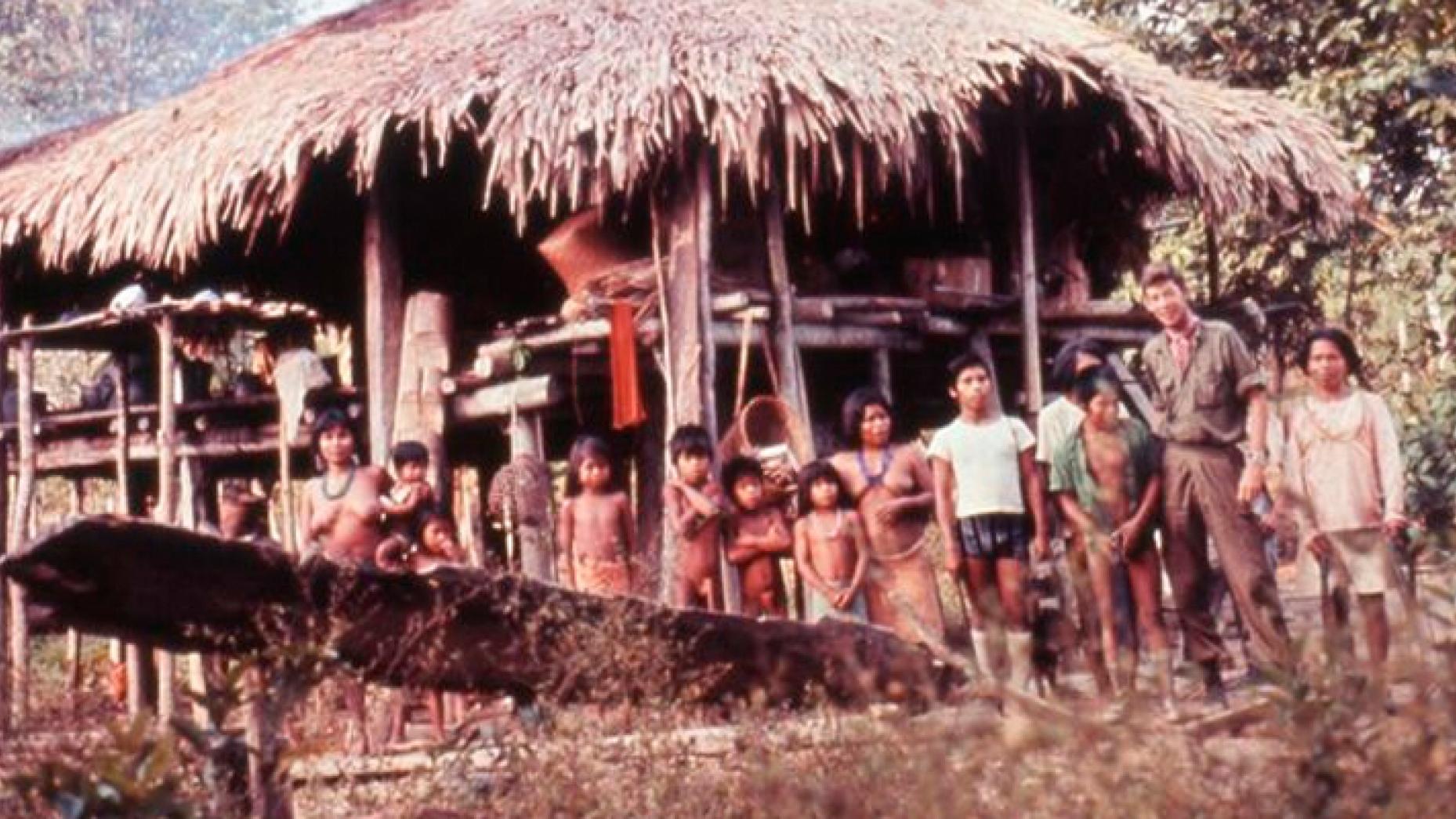

Stretching between Panama and Colombia, the Darién was - and remains - diabolical: a 400km stretch of swampy, malaria-ridden jungle populated by deadly snakes and vampire bats. No bridges, no roads, no tracks, just a Britain-sized clump of impenetrable undergrowth, unmapped and unknown to any humans but the handful of tribes inhabiting the forest.

In fact, Thompson’s mission was even grander than conquering the Darién Gap. It was the first to drive the length of the Americas: 27,000 kilometres from Anchorage in Alaska to the southernmost tip of South America.

Thompson’s team of six men and two Range Rovers - launched the previous year - was dropped by military Hercules into Anchorage in December 1971, straight into the depths of an Alaskan winter.

The schlep through the USA down to Panama passed, in Gavin’s words “uneventfully”. This lack of events included one of the Range Rovers being decapitated on a frozen Canadian highway after skidding into a truck on sheet ice (they repaired it) and getting shot at in Nicaragua (they didn’t get hit). At the very south of Panama, hundreds of miles down a deserted dirt track, the expedition hit a wall of jungle. The Darién.

Before entering the dense, sweaty wilderness, the Range Rover team collected an expedition party of 64 men: a mix of Royal Engineers and scientists. The plan was to cross the Darién Gap in the dry season, but the rains persisted for weeks longer than expected.

This spelled tortuously slow progress through the clammy undergrowth: barely a mile a day, at times. A gang of Royal Engineers would tramp a path first, hacking and sawing a route for the Range Rovers to crawl along. Gavin would edge the first Rangie inch-by-inch down the rough trail, a fellow officer walking ahead of the front bumper to warn of drops and rocks.

After a hundred metres or so, he’d hop out of the first Range Rover and walk back for the second. A few days into the jungle, and things started to go bang. Bogging down in thick mud, the lead Range Rover’s front differential shattered, rapidly followed by the rear and the front diff of the second car. “We were told it was swamp, so we put big swamp tyres on. It wasn’t swamp; it was mud. The tyres created so much inertia they cracked the planet wheels.” Gavin radioed an SOS to Rover HQ. After simulating a jungle course in Solihull (the mind boggles), the Leyland engineers flew out a bunch of new diffs and standard off-road tyres. It did the trick.

Even with the Rangies running smoothly, conditions remained hellish. Scorpions and vicious biting ants were just the start: vampire bats gorged on the party’s horses, while white-lipped peccaries - brutish, wild pigs that roamed in herds of hundreds and attacked anything that moved - laid siege to the camp. Malaria and fever spread through the party; engineers developed trench foot from trudging through mud for 12 hours a day.

Supplies were air-dropped into the forest: 10 tonnes of rations, 15,000 gallons of fuel, 2,400 cans of beer, 80,000 cigarettes. The Range Rovers were driven everywhere possible, but many of the swamp’s hundreds of rivers could only be crossed by boat.

To get the cars across, ladders were lashed atop the expedition’s two Avon rafts, onto which Gavin would inch a Range Rover and sit on board as it was dragged across the water, holding the brakes and hoping not to fall in.

He fell in. Deep in the jungle, being towed across a river hundreds of metres wide, the makeshift raft caught a current and toppled over, the Range Rover plunging into the water as Gavin scrambled out of the driver’s window.

By the time the crew had attached a winch to the car and dragged it to dry land, the car was entirely waterlogged. “I let it drain out and got a load of oil parachuted in”, says Gavin. “The only thing that didn’t work was the cassette player…”

On a stifling morning in late April, just before the rains returned, the men emerged, bedraggled, from the south side of the Darién swamp. Gaunt and damp, most members of the party had lost stones in weight.

It had taken 100 days precisely to cross the Darién Gap. Free of the jungle, Gavin’s team of six ditched the scientists and engineers, and gave it the beans all the way through South America, covering hundreds of miles a day on tarmac roads.

On 9 June 1972, six months after setting out from Anchorage, the two Range Rovers reached the end of the 27,000km road, the southernmost tip of South America. Gavin’s team cracked open a bottle of champagne, had a quick swig… and then pelted back to Buenos Aires to catch a flight home. They paid five quid each for their plane tickets.

The Trans-America expedition was not only the most ambitious road trip in history, but also the ultimate baptism of fire for the newborn 4x4.