What is it?

Thought the e was Honda’s first production EV? Think again. Honda started working on EVs in the late Eighties – the last major Japanese carmaker to do so – and wound up releasing its first attempt in 1997.

Like most other Nineties electric cars such as the GM EV1 and Toyota RAV4 EV, in reality the Honda EV Plus served a very specific purpose. It was a compliance car, built mainly to satisfy a mandate issued by California’s Air Resources Board (CARB) that said starting in 1998, two per cent of a car manufacturer’s sales in the state would have to be EVs.

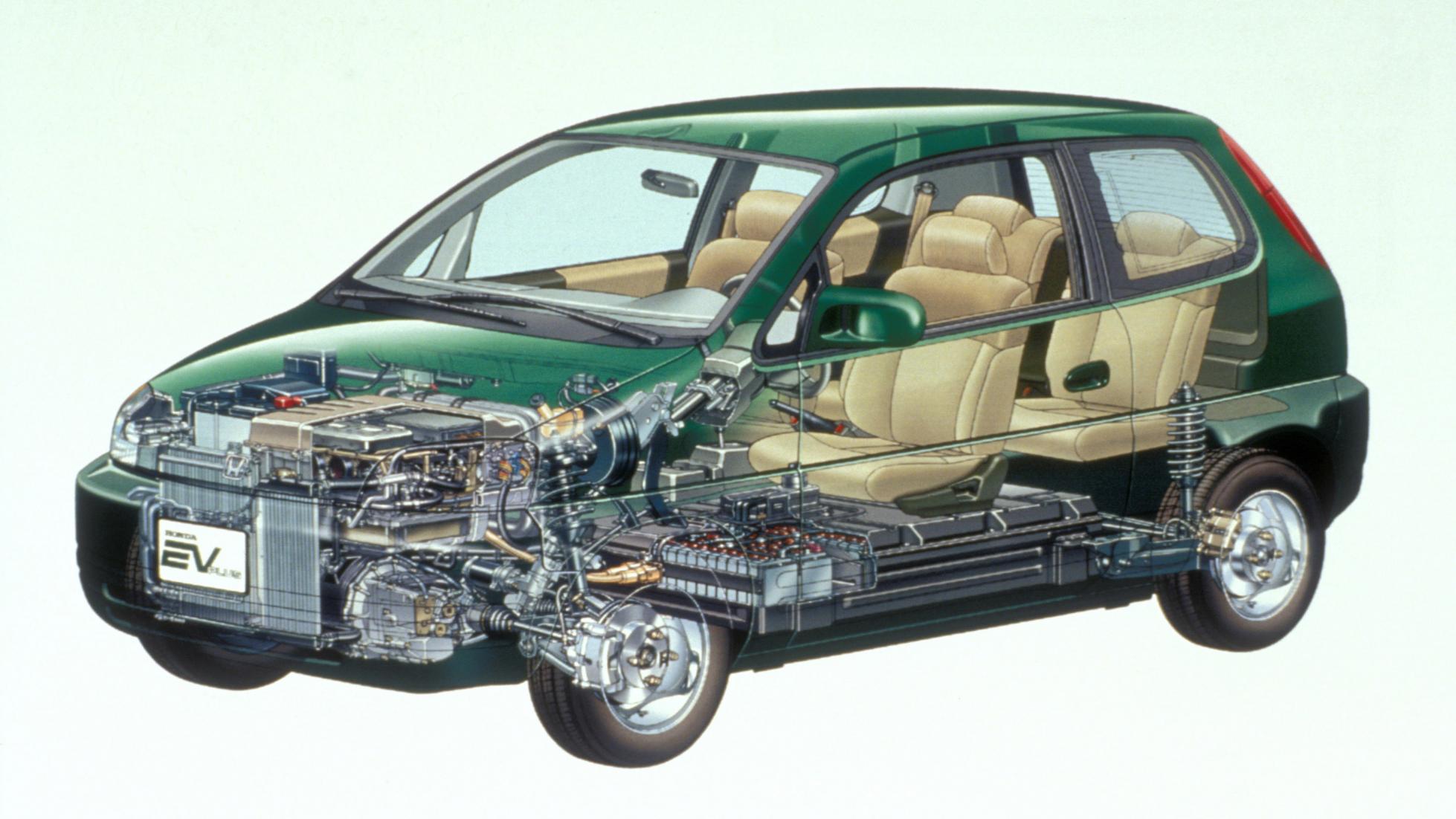

That said, it’s actually a pretty interesting car on a technical level. Probably among the more thoughtfully-engineered EVs of its era.

What technology did it use?

The Honda EV Plus was the first electric car from a mainstream manufacturer to use a nickel-metal hydride (NiMH) battery. Honda claimed the 28.7 kWH battery, which weighed almost half a tonne, had “twice the energy and life span” of the lead-acid batteries fitted to most other EVs of the era.

But it’s not like the EV Plus could travel much further on a single charge. Honda cautioned owners to expect between 95 and 128km of range, with the EPA officially rating the EV Plus at 130km, however tests found exceptionally careful driving (and switching the air-con off) could eke out 160km of driving.

A 220-volt power supply could deliver an 80 per cent charge in two hours, while a full charge on a normal household socket was said to take around 24 hours.

Was it fast?

The EV Plus’ electric motor made just 67hp (like a kei-car), so no, it really wasn’t fast. The four-seater, three-door, 1600+ kilogram hatchback could reach 48km/h in 4.9 seconds. Its top speed was said to be “over 130km/h”.

Was it cheap?

Again, no. The new-fangled (for the era) NiMH battery added an estimated US$20,000 to the EV Plus’ MRSP. Its list price was US$54,000, which was/is a hell of a lot of money, but Honda wouldn’t let anyone buy one outright.

You had to lease one for three years at just shy of US$500 a month. At least then you weren’t on the hook for replacing the battery, which supposedly was necessary every three years.

Honda leased 330 in total, and promised to “continue indefinitely to service and re-lease them”. Some lessees were able to hold on to their cars for a while after their agreements were up, but all cars were eventually recalled, decommissioned and destroyed as Honda elected to concentrate on hybrids.

At the time, the company said it had no plans to make another EV until there was a “significant improvement in the technology that now limits cars such as the EV to 80 miles between eight-hour charging periods”.

Tech from the EV Plus programme was used to develop fuel-cell vehicles.

Tell me something interesting about it.

The EV Plus has something in common with the VW ID.R. Beyond the fact they’re both electric, obviously.

Yup – the EV Plus once held the record for the fastest electric car to complete the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb. Teruo Sugita drove the 12.42-mile (or a perfectly round 20km) course, then a mixture of asphalt and gravel, in a modified EV Plus ‘Type R’ in 15 mins and 19 seconds.

What electric cars does Honda make now?

Just one – the brilliant Honda e. Sure it’s compromised – it can’t go very far on a charge, it’s not very spacious and it’s not cheap – but you can’t help but fall for it. Expect many more electric Hondas to arrive in the next few years.

Why did it fail, and what did we learn from it?

Same reason its contemporaries failed – when the CARB mandate was slackened, manufacturers elected to abandon the EVs they’d been effectively forced to build (at pain of being barred from selling any cars in California).

These EVs were expensive to develop and maintain (battery replacements aren’t cheap) and demand was low. Honda, like Ford, Toyota and GM, chose to recall and destroy the few cars it had released into the wild.

Had California been able to keep the mandate as it was originally written, and manufacturers had no choice but to continue developing pure EVs through the Nineties and early Noughties, might we all be driving affordable 800km EVs by now? Who knows.

STORY Tom Harrison