8 things you might not know about the original Mercedes W198 SL

01 You can thank the Americans for it

Well, technically one American. And even more technically, he was born in Austria. But let’s not worry about incessant details when we have this very broad brush with which to paint colourful strokes.

The fact is that Max E Hoffman was as much of a New Yorker as anyone else in that concrete jungle in which dreams are made. Yeah, proper grammar, popular music. Try it.

But you can also thank Americans at large, who were much like the Chinese are now – numerous and wealthy enough for manufacturers to build special one-offs and reasonably expect to make their money back.

Max Hoffman had to put in an order for 1000 SL road cars before Mercedes would agree to build them, after all. And he was far too canny to do that without knowing he had a market to match.

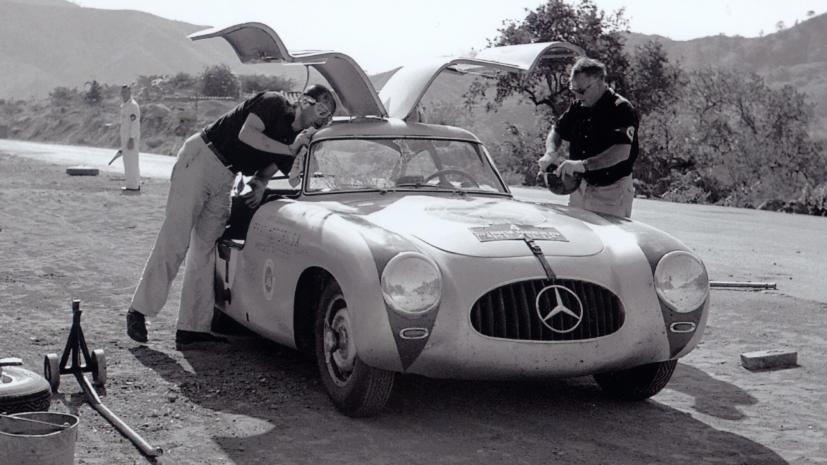

02 It was based on a race car

And not just any race car, either – the very first Mercedes built to be supremely lightweight (hence the introduction of the SL or ‘Super Light’ designation) and perhaps one of the most broadly successful race cars of all time.

This might take a bit of explaining. A Formula One car, for instance, tends to do well on spotless, groomed tracks, but would likely struggle in the Acropolis Rally. Similarly, a Trophy Truck is the absolute business somewhere like the Baja Peninsula, but is comically entertaining around a sealed race track.

But the Mercedes 300SL race car was properly quick on road courses like the Mille Miglia, on race tracks like Le Mans and the Nordschleife, and even on the gravel stages of the deadly Carrera Panamericana. And with a foundation like that, is it really any wonder Mercedes kept as much of the original car as possible for its road-going sportscar?

03 It took Mercedes just six months to create the SL road car

Yep, the most hallowed and hankered-after SL of all took just six months to go from an idea in Max Hoffman’s head to a pair of near-production models on the stand at the New York motor show.

Yes, Merc had a racing car to go off, but think about how long it’s taken for AMG to convert Hamilton’s old F1 car to be useful on the road. Not such an easy task, is it?

04 You can thank Max Hoffman (and the Americans) that there’s a convertible version, too

Max Hoffman was not exactly what you’d call Mad Max. More like Overtly Sensible Max. Forward-Thinking Max. Pragmatic Max. Oddly Prescient Max. You get the gist.

Almost as soon as the Gullwing SL knocked everyone’s socks off – and had a meaningful attempt at their shoes as well – Herr Hoffman started advocating for a drop-top SL as well.

So, if it weren’t for those cashed-up Americans in the Fifties – and their seemingly boundless appetite for cars with 60 miles of headroom – the defining characteristic of the modern SL might never have been.

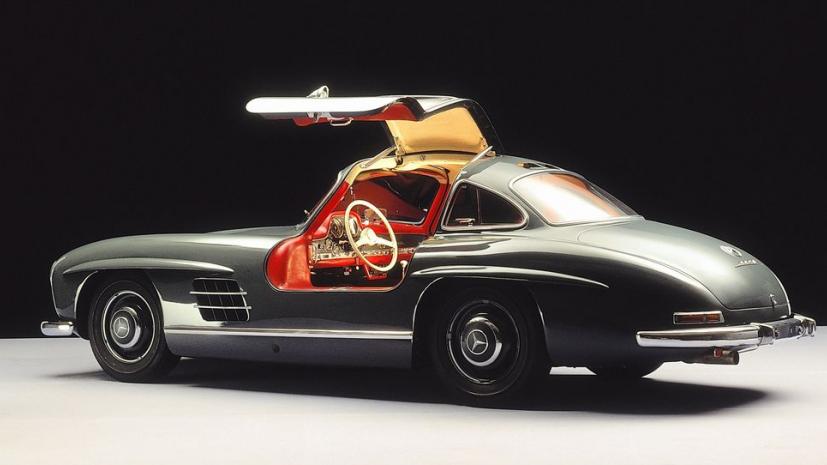

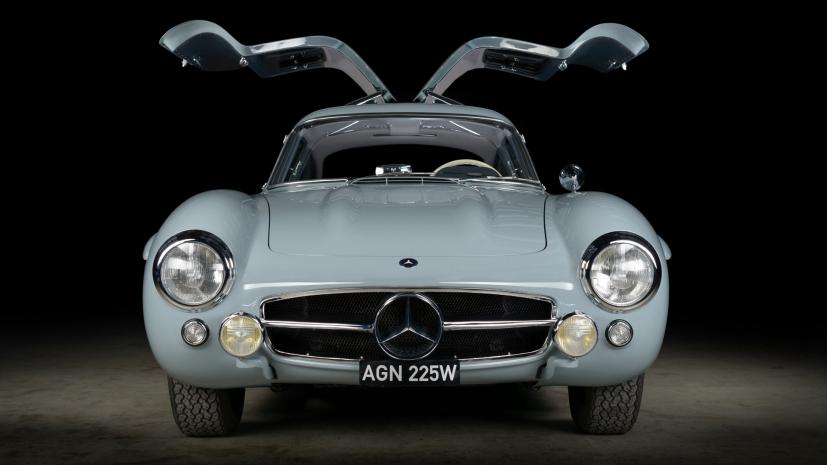

05 Those gullwings weren’t there to look pretty

Although it’s hard to say they didn’t do a fantastic job at that anyways. The reason the SL was bewinged was because the race car chassis had incredibly high and wide sills, added to give the featherweight, 50kg space frame rigidity. The entire race car, in fact, weighed just 870kg, thanks in part to Mercedes’ liberal use of aluminium.

But back to those sills. When we said “incredibly high”, it wasn’t just due to our inability to describe something without resorting to hyperbole. The sills are halfway up the side of the car, right at the waistline.

So putting regular doors on would have been about as effective and graceful as doggy doors. So the gullwing doors, while they might be fantastical, aren’t whimsical, but entirely practical. Radical.

06 The convertible 300SL was actually a better car than the Gullwing

Yeah, yeah, we know. Sacrilege and all that.

But the 300SL roadster drove better, thanks to revised rear suspension that offered better grip and fewer opportunities to meet your maker long before you’d intended.

The gearbox got synchros for easier shifting, the spare wheel was relocated so you actually got some luggage space in the boot, and you also got the option of seatbelts, a removable hardtop, Dunlop disc brakes and a lighter alloy engine block.

There’s also the little-known fact that Merc’s gullwing doors had a habit of leaking water through the hinges after a while. So you could be slightly damp as you went off the road backwards.

So the Roadster drove better, was safer, had better equipment and, despite being a convertible, actually kept the elements out more reliably. You would imagine, then, that the better car would be worth more, wouldn’t you? Oh, silly rabbit. Sensical classic car values are for kids.

07 Andy Warhol made artworks out of it

And this was the guy who painted a tin of Campbell’s soup. Clearly, we’re dealing with a special car.

So, after perhaps the most reductive explanation of one of art’s true luminaries, let’s instead give the SL and the artist the credit they’re due. Warhol was an icon of Pop Art, a celebrated author and filmmaker, and – let’s be honest here – a masterful marketer.

But what’s often overlooked is how much of a documentarian he was as well. As a first-year art history student would say, Warhol recognised and immortalised both the zeitgeist and cultural icons of his era, producing artworks that featured global phenomena from Marilyn Monroe to Mao Zedong.

He was also not the sort to knock back commissions, either – something the canny chaps at Mercedes made the most of. Really, if you’re going to get someone to immortalise your car, could you go past one of the most famous and revolutionary artists of all time?

Check out Mercedes’ archive of Warhol’s commissioned works here and here and tell us you haven’t found some properly tempting options to hang on your wall.

08 The 300SL road car was actually more powerful than the race car

Even though the road car was hugely heavier than its racing counterpart, it still managed to be just as fast. And, if you’ve got a bit of an idea about Merc’s modus operandi, you won’t be surprised to learn that it’s purely down to extra lashings of power.

While the race car used Mercedes’ biggest engine in the Fifties – a heavily modified version of the 3.0-litre straight-six from the appropriately named Model 300 sedan – it still ran carburettors, as was the style at the time.

The road car, on the other hand, used Bosch mechanical fuel injection, a tremendously complicated system that nonetheless bumped power up from 175bhp in the carb-fed race car engine to 215bhp (and as much as 240bhp later on) in the road-going SL.

STORY Craig Jamieson